Figure 1

[This appeared in the Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 9:1 [Winter 1993-94]. It also won First Place, Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication Ethics Prize, 1993, Undergraduate Division. (I had to take media ethics class to meet a general education requirement while an undergraduate -- and the prize money paid my tuition that semester!) I have made a couple of minor arithmetic corrections in Table 1 that do not affect the conclusions of the paper.]

Back to my web page

ABSTRACT: Analyzes news coverage of mass murders in Time and Newsweek for the period 1984-91 for evidence of disproportionate, perhaps politically motivated coverage of certain categories of mass murder. Discusses ethical problems related to news and entertainment attention to mass murder, and suggests methods of enhancing the public's understanding of the nature of murder.[1]

On January 17, 1989, a homosexual prostitute and drug addict with a long history of criminal offenses and mental disturbance, Patrick Purdy, drove up to Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California. He firebombed his car, entered a playground during recess carrying a Chinese-made AKS (a semiautomatic version of the full automatic AK-47), shot to death five children, wounded 29 other children and a teacher, then shot himself in the head with a 9mm handgun.

Initial coverage of Purdy's crime was relatively restrained, and only the essential details were reported. Time gave Purdy only part of a page in the first issue after the crime ("Slaughter in a School Yard", 1989). Newsweek gave a single page to "Death on the Playground," and pointed to four prior attacks on school children, starting with Laurie Dann. Purdy's photograph was included in the Newsweek article. Newsweek's article (Baker, Joseph, and Cerio, 1989) quoted one of the authors of a book on mass murder: "There's a copycat element that cannot be denied."

But a week later, Patrick Purdy's name continued to receive press attention, and consequently his fame increased. The front cover of Time showed an AK-47 and an AR-15 crossed, beneath an outline of the U.S., stylized into a jawless skull, entitled, "Armed America." Inside, George Church's "The Other Arms Race," (1989) which occupied slightly more than 6½ pages, opened with Patrick Purdy's name. Articles referencing Purdy or his crime continued to appear in both Newsweek or Time for many months.

On September 14, 1989, Joseph Wesbecker, a disabled employee of Standard Gravure Co. in Kentucky, entered the printing plant carrying an AKS and a 9mm handgun. How profoundly similar Wesbecker's actions were to Purdy's was shortly detailed by UPI wire service stories, such as William H. Inman's "Wesbecker's rampage is boon to gun dealers" (1989a):

So he bought an AK-47, a Chinese-made assault rifle firing 7.62mm rounds capable of blowing holes in concrete walls. He used a picture to describe the gun to a local dealer, who ordered it through the mail.

Wesbecker, police say, was already planned a massacre of his own -- one which killed eight Thursday and wounded 13. He used an AK-47 on all victims but himself. He committed suicide with a pistol.

In the same way Wesbecker's interest was peaked[sic] -- he had clipped out a February Time magazine article on some of Purdy's exploits -- gun dealers expect a renewed blaze of interest in the big gun.

"With all the media attention since then," said Ray Yeager, owner of Ray's Gun Shop in Louisville, "and all the anti-gunners's attempts to ban (assault rifles), the result has been massive sales." [2]

"Calendar of Senseless Shootings."

The major gun purchases were made between February and May.

Initially police thought Wesbecker was an ardent gun handler or paramilitary buff, but evidence indicates his interest in guns was relatively young.

"We have no information indicating he had a collection of guns, or was even interested in them before last year," said Lt. Jeff Moody, homicide investigator. "As far as we know he had no formal training in weapon use." (Inman, 1989b)

Nor was it that no one in the media saw a connection between Wesbecker's reading material and the crime. The Los Angeles Times, the Press-Democrat, and the New York Times all suggested a connection between Wesbecker's actions and Soldier of Fortune magazine. Wesbecker had taken to reading Soldier of Fortune, but none of the articles indicate that Soldier of Fortune had been found in such an incriminating position as the Time article (Harrison, 1989). Apparently, Soldier of Fortune's mere presence in Wesbecker's home was an important piece of news, while the marked-up copy of Time, left open, wasn't important enough to merit coverage. Of the four newspapers examined for coverage, only the San Francisco Chronicle included the disturbing connection between Time's coverage and the crime:

But even absent a notion of legal responsibility, there should be a notion of moral responsibility, and awareness of a causal relationship should provoke concern among journalists. Joseph Wesbecker, without question, was headed towards some sort of unpleasant ending to his life. But in the absence of the February 6th coverage by Time, would he have chosen this particular method of getting attention? Wesbecker was under psychiatric care at the time, and had already made three suicide attempts (Inman, 1989b). Did Time's sensational coverage, transforming the short unhappy life of Patrick Purdy from obscurity to permanent notoriety, encourage Wesbecker to transform the end of his life from, at most, a local news story of a suicide, into a story that was carried from coast to coast?

Newsweek and especially Time, perhaps for reasons of circulation, perhaps for political reasons, have engaged in ethically questionable practices in recent years in their coverage of mass murder in the United States. These practices were unquestionably a major cause of the murder of seven people in 1989, and may have played a role in the murders of others in recent years. The actions they took provide a concrete example of a problem in media ethics that is at least two centuries old: how much coverage should the press give to violent crime?

There are three related ethical problems that will be addressed in this paper:

1. The level of coverage given by Time and Newsweek (and perhaps, by the other news media) to certain great crimes appears to encourage unbalanced people, seeking a lasting fame, to copy these crimes — as we will see indisputably happened in Joseph Wesbecker's 1989 homicidal rampage.

2. Analysis of the quantity of press coverage given to mass murder suggests that political motivations may have caused Newsweek and especially Time to give undue attention to a particular type of mass murder, ultimately to the detriment of public safety.

3. The coverage given to murder by Newsweek and Time gives the electorate a very distorted notion of the nature of murder in the United States, almost certainly in the interests of promoting a particular political agenda.

Fame and infamy are in an ethical sense, opposites. Functionally, they are nearly identical. Imagine an alien civilization that does not share our notions of good and evil, studying the expanding shell of television signals emanating from our planet. To such extraterrestials, Winston Churchill and Adolph Hitler are both "famous"; without an ability to appreciate the vituperation our civilization uses to describe Hitler, they might conclude that both were "great men." Indeed, they might assume that Hitler was the "greater" of the two, because there has certainly been more broadcast about Hitler than about Churchill. The human need to celebrate human nobility, and to denounce human depravity, has caused us to devote tremendous attention, both scholarly and popular, to portraying the polar opposites of good and evil.

The pursuit of fame can lead people to acts of great courage and nobility. It can also lead to acts of great savagery. The Italian immigrant Simon Rodia, builder of Los Angeles' Watts Towers, once explained that his artistic effort was the result of an ordinary person's desire for fame, because, "A man has to be good-good or bad-bad to be remembered." ("Simon Rodia, 90, Tower Builder", 1965) But for most people, fame isn't as easy as building towers of steel, concrete, and pottery. Unfortunately, being "bad-bad" is easier than being "good-good" — as history amply demonstrates.

In 356 BC, an otherwise unremarkable Greek named Herostratus burned the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in an effort to immortalize his name. That we remember the name of this arsonist, the destroyer of one of the Seven Wonders of the World, shows that great crimes can achieve lasting fame (Bengston, 1968, p. 305; De Camp, 1963, p. 91; Coleman-North, 1963, 10:414). [3] Fisher Ames, a Massachusetts Federalist who sat in the House of Representatives from 1789 to 1800, expressed his concerns about this very subject in the October, 1801 issue of the Palladium:

Every horrid story in a newspaper produces a shock; but, after some time, this shock lessens. At length, such stories are so far from giving pain, that they rather raise curiosity, and we desire nothing so much as the particulars of terrible tragedies (Allen, 1983, pp. 14-15).

Mass murder isn't new to America (or anywhere else) ¾ nor is the popular horror and interest in such crimes. Consider the following children's doggerel about the 1892 murders in Fall River, Massachusetts ("Borden, Lizzie Andrew", 1963, 4:266):

In the 1980s, there were a number of mass murders in the United States, and yet the quantity of press coverage for these crimes varied widely. All other things being equal, when mass murder is committed in this country, we should expect the coverage to be generally proportionate to the number of victims. How do we measure the quantity of press coverage for a major crime? The more remote a newspaper is from a crime, the less extensive the coverage we should expect. As a result, it would not be a meaningful measure of the quantity of press coverage to examine any sort of local or even regional newspaper coverage; the coverage of a West Coast crime in California newspapers will doubtless be far greater than coverage of a similar crime that took place on the East Coast. A more meaningful measurement is the press coverage given by the national news magazines, such as Time and Newsweek.

An analysis of articles in Time and Newsweek, America's mass circulation news magazines, shows some interesting characteristics of how mass murder in America is covered. For the purposes of this paper, any article which mentioned a mass murderer, even by referring to his specific criminal act, was considered to be "fame" in the sense we defined earlier in this paper. Even if the article was primarily about some related subject, if the mass murderer was mentioned, the entire article was considered as adding to that killer's fame.

Why the entire article? Because a potential mass murderer will consider any future article that mentions him to be "publicity." Wesbecker demonstrated this by leaving open in his room the February 6th Time article. Although the article was primarily about gun control and mass murder, it included Purdy's name and crime as part of the introduction.

Attempting to locate articles that refer to these mass murderers is difficult, because many of these articles are not locatable by keyword search. In the case of mass murderers who used guns, I looked through all the articles during the period 1984-1991 that were about gun control or mass murder, and I included only those that referenced the murderers or their crimes. For arson murders, I looked up articles about arson and fire hazards. Articles purely about gun control or fire hazards that failed to mention these mass murderers by name or action, were not included in the analysis. For mass murders committed with other weapons, I looked up appropriate articles about the weapon used, as well as articles about mass murder.

The criticism could be made that even a brief mention of a mass murderer's actions in a larger article will tend to exaggerate the level of coverage given to that crime. This is a valid concern, but as long as all categories of mass murder receive identical treatment, the results should be roughly equivalent. Where an article contained no mention of the mass murderer or his actions, and a sidebar article did, only the sidebar article was included in the computation of the space given.

What constitutes mass murder? This is important, because by manipulative definition of "mass murder," one can prove nearly anything about the news coverage. Clearly, there is a difference between serial murderers, and mass murderers, and a difference that makes them non-comparable from the standpoint of analyzing the news coverage. The difference is that serial murderers commit their crimes over a very long period of time, and so each murder is, by itself, a minor story. Also, because serial murderers sometimes are successful in making the remains of the victim disappear, the only news story is when that serial murderer's actions are finally noticed.

For these reasons, and for the purposes of this paper, a mass murder has two distinguishing characteristics:

1. Actions intentionally taken, with the expectation that great loss of life will result, or where any reasonable person would recognize that great loss of life will result. The component of expecting loss of life, of course, is a fundamental part of the question of whether publicity plays a role in promoting such crimes.

For this reason, I have excluded such tragedies as Larry Mahoney's drunken driving motor vehicle wreck that caused 27 deaths in May of 1988. Mahoney was convicted of manslaughter, so the essential element of premeditation was lacking, except in the sense that getting drunk and operating a motor vehicle is potentially quite dangerous ("Convicted. Larry Mahoney", 1990). However, including crimes like Mahoney's in this study would tend to strengthen my argument that Time and Newsweek give special treatment to firearms mass murderers, since Mahoney received no press in Newsweek, and only 0.15 square inches per victim in Time.

2. The actions causing the loss of life all take place within 24 hours, or the deaths are all discovered within 24 hours. This is an arbitrary period of time, of course. It could have been extended to 48 hours, or 72 hours, however, without significantly widening the bloody pool of crimes whose coverage we will study.

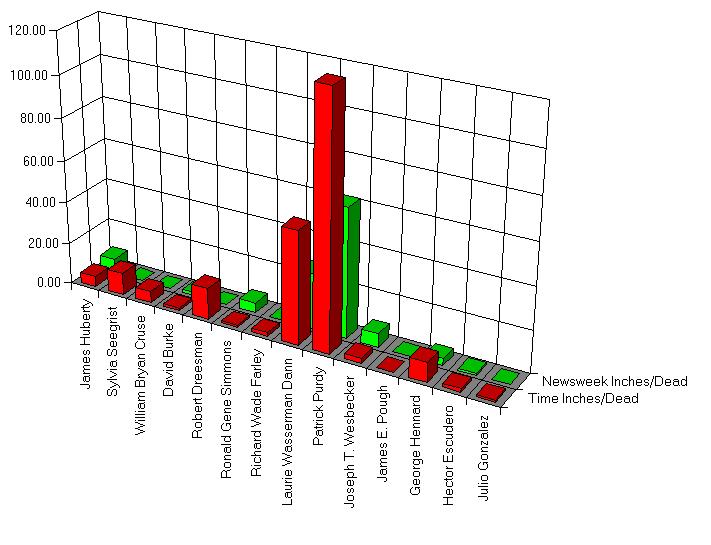

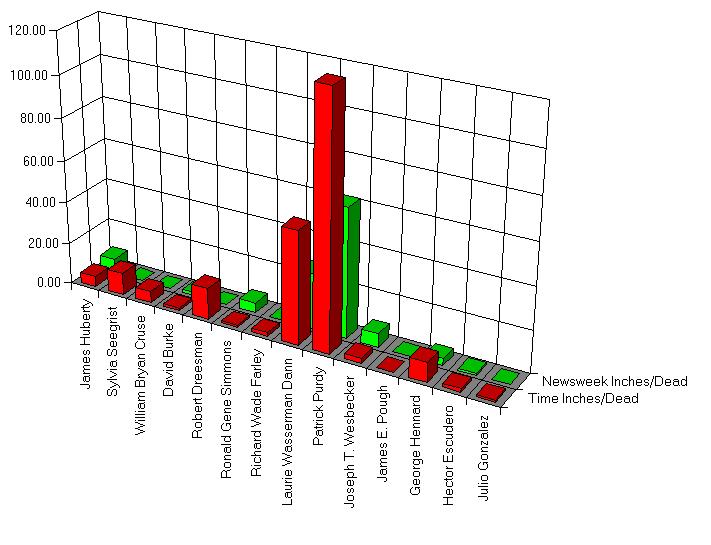

Most people I talk to are quite surprised

to find out that there are mass murderers who kill with weapons other than

guns. They are even more surprised when they find out that arson mass murder

victims in the last few years have outnumbered gun mass murders. Why is

this a surprise? The reason is that press coverage of non-firearms mass

murders is almost non-existent. As Table 1 shows, arson mass murderers

and knife mass murderers receive relatively little attention from Time

and Newsweek. As should be obvious, there is a very large discrepancy

between the amount of coverage given to arson mass murders, and mass murderers

involving guns exclusively. [4]

Almost nine times as much coverage were given to exclusive firearms mass

murderers, as to arson mass murderers.

| Murderer | Month/Year | Dead | Time sq. in. | Time Sq. Inches/Dead | Newsweek sq. in. | Newsweek Sq. Inches/Dead | Total Sq. Inches/Dead |

| James Huberty |

Jul-84

|

22

|

109.63

|

4.98

|

157.50

|

7.16

|

12.14

|

| Sylvia Seegrist |

Nov-85

|

2

|

20.75

|

10.38

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

10.38

|

| William Bryan Cruse |

Apr-87

|

6

|

33.06

|

5.51

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

5.51

|

| David Burke |

Dec-87

|

43

|

52.50

|

1.22

|

57.75

|

1.34

|

2.56

|

| Robert Dreesman |

Dec-87

|

7

|

105.00

|

15.00

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

15.00

|

| Ronald Gene Simmons |

Dec-87

|

16

|

15.94

|

1.00

|

78.75

|

4.92

|

5.92

|

| Richard Wade Farley |

Feb-88

|

7

|

11.25

|

1.61

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

1.61

|

| Laurie Wasserman Dann |

May-88

|

2

|

107.63

|

53.81

|

54.00

|

27.00

|

80.81

|

| Patrick Purdy |

Jan-89

|

6

|

720.00

|

120.00

|

370.34

|

61.72

|

181.72

|

| Joseph T. Wesbecker |

Sep-89

|

8

|

19.69

|

2.46

|

52.50

|

6.56

|

9.02

|

| James E. Pough |

Jun-90

|

9

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

| George Hennard |

Oct-91

|

24

|

225.00

|

9.38

|

78.75

|

3.28

|

12.66

|

| Firearms Murders |

152

|

1420.44

|

9.34

|

849.59

|

5.59

|

14.93

|

|

| Firearms Murders excl. Patrick Purdy |

146

|

700.44

|

4.80

|

479.25

|

3.28

|

8.08

|

|

| Ramon Salcido |

Apr-89

|

7

|

78.75

|

11.25

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

11.25

|

| Knife/Gun Murders |

7

|

78.75

|

11.25

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

11.25

|

|

| Hector Escudero |

Dec-87

|

96

|

155.63

|

1.62

|

78.75

|

0.82

|

2.44

|

| Julio Gonzalez |

Apr-90

|

87

|

76.63

|

0.88

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

0.88

|

| Arson Murders |

183

|

232.25

|

1.27

|

78.75

|

0.43

|

1.70

|

Table 1

A large part of this discrepancy, however,

is because of the many articles that mentioned Patrick Purdy's crime. But

even excluding all coverage of Patrick Purdy's crimes (a very charitable

assumption for Time and Newsweek, considering the centrality

to Wesbecker's actions of Time's coverage), the square inches per

dead body for firearms mass murderers is still 4.75 times the coverage

for the arson mass murderers. Plotting the square inches per dead body

coverage by murderer shows how dramatic a difference this was.

Figure 1

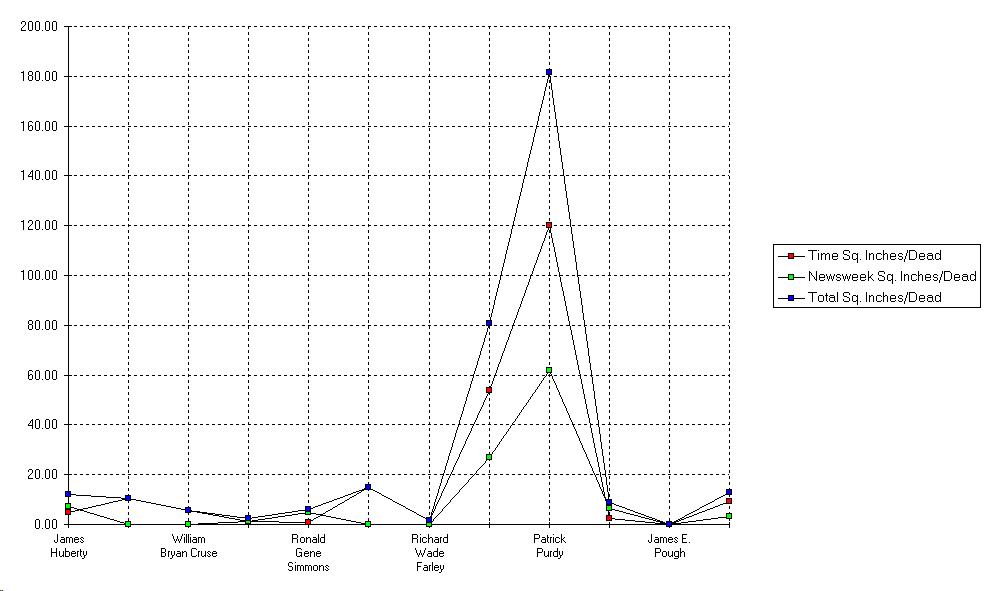

Plotting the firearms mass murder

coverage against time also shows some interesting results, as Figure 2

shows. As should be obvious, mass murder coverage rose dramatically with

the crimes of Laurie Wasserman Dann and Patrick Purdy — and suddenly dived

back to the pre-Dann levels with the Wesbecker incident. Time, more

prone to covering firearms mass murders before Dann and Purdy, was the

more noticeably restrained of the two magazines in its coverage of mass

murders from Wesbecker onward. Did someone at Time see the connection

between their coverage of Purdy, and Wesbecker's bloody rampage?

Figure 2

Was Wesbecker just one amazing case? While considerable energy has been devoted by the academic community to research on the effects of violent entertainment on aggression, a search of the available literature suggests that the influence of news coverage on aggression has not been examined. The only work even remotely related to this topic is Cairns' study (1990) of how television news coverage of political violence influenced children's perceptions of the level of political violence in Northern Ireland. The study made no attempt to determine what effect, if any, this news coverage had on levels of violence or aggression among the children themselves.

In the area of entertainment violence, a rich scientific literature exists, but serious questions exist as to its applicability to the effects of news coverage on adults. Those studies that attempted to evaluate the effects of regular televised entertainment violence either explicitly excluded special news programs that appeared in prime time (Price, Merrill, and Clause, 1992), or implied that only entertainment programs were rated for violence (Harris, 1992).

The applicability to adults of the research that has been done regarding violent entertainment's effects on children is also a troubling question. Wood, Wong, and Chachere's paper (1991) which summarized the existing research on children, aggression, and media violence, concluded that the results demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between media violence and subsequent aggressive behavior, but also admitted:

More troubling about these studies is that a critical reading suggests the researchers approached the problems with a goal to prove a particular point, and assumptions so heavily loaded as to prevent an accurate assessment of the significance or validity of information.

One rather obvious example is David Lester's 1989 study, "Media Violence And Suicide and Homicide Rates." This one page article summarizes two reports from the National Coalition on TV Violence. The first report asserted a negative correlation between suicide and violent, top 10 best-selling books (apparently in the U.S.) from 1933 to 1984, and a positive correlation to homicide during that same period. The second report asserted similar, but not statistically significant relationships between best-attended films and suicide and homicide. That the National Coalition on TV Violence is a less than objective source on this topic should be obvious, but this does not preclude it being a valid source. Unfortunately, Lester made no attempt to analyze the methods used, or critically evaluate the significance of these reports.

There are serious problems proving or disproving a causal relationship between television entertainment and violent behavior, and there is no reason to assume that television news provides any easier opportunity for such research. But even though we can't prove that the coverage of Purdy's crime provoked Wesbecker, the evidence found in Wesbecker's home should make managing editors ask themselves, "What should we do about this?" The editors of Time should especially ask themselves, "Would less sensational coverage of Patrick Purdy have prevented the massacre at Standard Gravure? What if we hadn't run the February 6th article?"

The ethical issues here are more than just how coverage of one crime causes a copycat crime. Not only did both Time and Newsweek give disproportionate coverage to firearms mass murder (relative to other types of mass murder), but even relative to other types of murder, mass murder is grossly overrepresented in the news magazines. In the years 1987-1991, a total of 96,666 people were murdered in the United States (FBI, 1992). Mass murder victims from our sampled articles during this period totaled 318. [5]Time and Newsweek, in order to give equivalent coverage to the other 96,348 murders, would have needed 693,657.12 square inches, or more than 42 pages per week between them!

There are reasons why mass murders are given exceptional coverage relative to other murders. The most obvious is that in many ordinary murders, there is insufficient information to determine who did it, or even who might have done it. In 1991, 34% of the murderers were a complete mystery to the police (FBI, 1992, p. 16). The tawdry little details of tens of thousands of murders would be mind-numbingly boring, especially without an explanation of who did it, and why; a news magazine that fails to entertain, fails to keep subscribers. (A less cynical explanation is that reporters simply don't consider these "little" murders to be newsworthy.)

An example of this approach is Time's "Seven Deadly Days." In this article, Time obtained photographs and details of every person killed by a gun in the week May 1-7, 1989. This included not only murders, but also justifiable homicides (both police and civilian), suicides and accidents. While this could have been a useful mechanism for providing the sort of balance needed to obtain a more complete picture of murder in the U.S., because it excluded the one-third of murders done with other weapons, the effect was severely unbalanced (Magnuson, Leviton, and Riley, 1989a). That the intent was to promote restrictive gun control laws was made clear in the article that followed, "Suicides: The Gun Factor." (Magnuson, Leviton, and Riley, 1989b)

It should be obvious that this problem of balance can't practically be achieved by expanding coverage of the "little" murders. But how can a news magazine achieve coverage that conveys the reality of murder in the U.S.? One way would be to either reduce coverage of these very atypical firearms mass murders, or dramatically enlarge their coverage of more typical murders. In looking through the Reader's Guide To Periodical Literature for the years 1984-91, it became obvious that murders involving guns were worth coverage in Time and Newsweek, while murders of equally minor importance to the nation committed with other weapons were simply not covered. In spite of the 17,489 murders committed with knives and other "cutting instruments" in the years 1987-1991 (about 18% of the total murders), these crimes are almost non-existent in Time and Newsweek. The same is true for the murders with blunt objects, hands, fists, and feet (11,088 in 1987-1991, or 11% of the total murders).

The net result is a very misleading understanding of what sort of murders are committed in the United States. My experience over the years, when engaged in discussions with journalists, elected public officials, and ordinary citizens, is that they are usually quite surprised to find that firearms mass murder is a rare event, and are even more surprised to find that more than one-third of U.S. murders involve weapons other than firearms (FBI, 1992, p. 17). This misunderstanding doubtless plays a part in the widespread support for restrictive gun control laws, and the relatively relaxed attitude about more general solutions to the problem of violent crime of all sorts.

Nor is this problem limited to the subject of murder and firearms. Meyer (1987, pp. 155-156) points to the problem of how unbalanced reporting of health and safety issues in the popular media causes wildly inaccurate notions of the relative risks of various causes of death. As an example, a surveyed group greatly underestimated deaths caused by emphysema, relative to deaths by homicide. Meyer describes a study done by researchers at the University of Oregon, which found "the pictures inside the heads of the people they talked to were more like the spooky, violent world of newspaper content than they were like the real world."

It is important that we recognize that this misleading portrayal of the real world is not only an artifact of popular morbid curiosity, which newspapers must satisfy or lose circulation, it may also reflect what Meyer calls, "The Distorting Effect of Perceptual Models." In brief, journalists (like the rest of the human race) bring certain assumptions to their work. Facts that do not fit into the journalist's perceptual model tend to be downgraded in importance, or ignored. When the facts include statistical analysis, at even the most basic level, the primarily liberal arts orientation of many journalists comes to the forefront, and the perceptual model takes precedence. (Meyer, 1987, pp. 48-50) Especially because of the deadline pressure of daily or weekly journalism, the opportunity for careful reflection about the validity of these perceptual models may not exist.

How should the news media respond? First of all, let us be clear on what is not appropriate: the government taking any action to regulate or limit news coverage. Even ignoring the First Amendment guarantee of a free press, there are sound pragmatic arguments against giving this sort of power to the government. This paper asks only ethical questions, not political or legal questions.

Governmental power to decide the "appropriateness" of news coverage of violent crime would almost certainly become a tool for manipulation in favor of the agenda of the moment. A government that sought to whip the populace into a frenzy of support for (depending on ideology) restrictive gun control laws, reduced protections of civil liberties, or even something as mundane as higher pay for police, could, and almost certainly would, use its power over press coverage of crime to achieve these goals.

The same power, of course, can be used by the news media, and I argue that Time and Newsweek engaged in exactly this sort of manipulative coverage in 1988 and 1989, attempting to get restrictive gun control laws passed, by exaggerating the significance of firearms mass murders. What would be the practical difference between a system where the government used regulatory authority in this way, and the current system?

The difference is that, even within the current system, diversity does still exist. While three of the four newspapers sampled chose to not cover the instructional influence of Time on Wesbecker's killing spree, at least the fourth newspaper let its readers know that there was more to the problem of mass murder in America than just the availability of guns. In a system where the government held this power, and shared the clear goal of Time and Newsweek, all four newspapers would have agreed with Time and Newsweek's coverage of this event.

Violent crime as entertainment serves no public interest. As art or simply as entertainment, amusements that portray violence can perhaps be justified. But we must remember that entertainment in the United States is a big business, and however much someone may justify slasher movies as "art," the real reason is profit, and lots of it.

In the recent film Grand Canyon, Steve Martin plays a director of "action" movies that contain violence, bloodshed, and lots of weaponry. Early in the movie, we see the director watching the studio's cut of his new film. He complains that they have cut out an essential piece of the scene: "The bus driver's head, brains on the window, viscera on the visor shot." Later in the film, after the director is shot and seriously injured by a robber, he realizes that his "art" is part of what cheapens and brutalizes life in modern America, and he decides that he would rather make quality films that promote humanistic values, instead of violent films that degrade the viewer. But by the end of the film, the director is reminded by his accountant that his "action" movies are very profitable, and the sort of films he wants to make won't support him in the sybaritic manner to which he has become accustomed. As a consequence, he again defends his films as "art," and resumes making bloody, gratuitously violent "action" movies (Kasdan, 1991).

Clearly, the writer and director of Grand Canyon were expressing their opinion about how profit corrupts people — and that violence on the screen helps to create violence on the street. (This sort of criticism of the current system from Hollywood insiders is especially telling.) While it is tempting to blame the producers of films that glorify violence, it is important to recognize that what makes violent entertainment profitable is that the audience for such films is very large. We have only to recall the popularity of the gladiatorial contests in the Circus Maximus, fought to the death, to see that the purveyors of such films are to some extent, captives of popular taste, and there is no reason to believe that these tastes are recently degraded.

On the other hand, news coverage of violent crimes does serve the public interest. How much coverage is necessary? Is it necessary to cover every violent crime, in the same level of detail?

In balance, coverage of crimes in our society can be a valuable tool for decision making. In the political realm, the electorate and their representatives may make rational governmental decisions based on news coverage. Individuals, properly informed, can make rational decisions about their personal safety. But when the population has been misled, intentionally or not, about the nature of the crimes in a society, and the rarity or commonality of those crimes, their decision making will be anything but rational. When the coverage is simply endless repetition of apparently meaningless tragedies, the numbing effect described by Rep. Ames doubtless takes its toll on our population today.

While the public interest may be the justification for the coverage of mass murders, profit is almost certainly the real motivation, because the mass media are in the business of making money. Should the mass media ignore mass murders?

No, because the news media are in grave danger of losing credibility if they simply pretend that bad things aren't going on out there. To the extent that our mass media play a part in acting as a watchdog on governmental actions, it is necessary that they be a Doberman, not a Basset hound. Ignoring mass murder would quickly destroy their credibility, simply because mass murder, especially in the last few years, seems to be an increasing part of Western culture. (This problem, unfortunately, is not limited to the United States. Canada, Britain, France, Australia, and Switzerland have all experienced such incidents recently, in spite of considerably stricter laws regulating firearms ownership in most of these countries.)

The problem of unintentionally promoting mass murder is a serious one. How should the mass media determine what is an appropriate level of coverage? Is it necessary to cover every such crime? Are there methods of discouraging the "shoot your way to temporary fame" approach? Unfortunately, this problem has not been adequately addressed in existing works on media ethics. A review of a number of recent works in this field suggests that while the general problem of psychological and economic harm caused by inaccurate or unethical reporting has been considered in great depth, this very severe form of harm — unintentionally encouraging mass murder — has not been specifically discussed.

Klaidman & Beauchamp (1987, pp. 93-123) discuss the issue of journalistic-induced harm, but only with respect to damaged reputations and business losses. While Klaidman & Beauchamp (pp. 201-7) also point to the problems of news organizations that create news events, including the problems of international terrorism, the possibility that a journalist's efforts might play a part in causing a specific murder, is not discussed. Lambeth (1986) while providing a very thorough theoretical model for addressing the ethical issues of journalism, also fails to address this specific problem of media-induced harm. Hulteng (1981, pp. 71-86) samples the ethical codes of a number of American newspapers; he also reprints the complete text of the codes of ethics for the Associated Press Managing Editors, American Society of Newspaper Editors, and the Society of Professional Journalists. While all address the issue of harm and balance in a general way, none directly discuss how coverage of a particular criminal act can lead to copycat crimes.

Can the news media satisfy both the obligation to accurately inform the public about the nature of America's murder problem, and the obligation to stockholders to keep circulation up, or does the inevitable public boredom with coverage of the tens of thousands of meaningless "little" murders make this an impossible balancing act?

The tradition of covering some murders in a sensational manner isn't new. Doubtless, editors will continue to justify this time-honored (or time-worn) tradition based on economic considerations. But in light of the major role that the disproportionate coverage of Patrick Purdy's crimes played in the bloody way that Joseph Wesbecker chose to end his life, editors need to ask themselves: "How many innocent lives will we sacrifice to boost circulation, or promote political agendas?"

Can we develop a code of ethics that resolves this problem? Let us consider the following as a first draft of such a standard: "A crime of violence should be given attention proportionate to its size, relative to other crimes of violence, and relative to the importance of its victim. Violent crime of all types should be given attention, relative to other causes of suffering, proportionate to its social costs." We must develop a strategy for dealing with this problem now — before another disturbed person decides to claim his fifteen minutes of fame.

Epilogue

Unfortunately, it happened again. As I was finishing revising this article for publication, Gian Luigi Ferri entered a San Francisco law office, murdered eight people, and wounded six others. When it became apparent that he would not escape the building alive, he killed himself. In his briefcase he had "the names and addresses of more than a dozen TV shows, including 'Oprah Winfrey,' 'Phil Donahue' and even 'Washington Week in Review.'" Ferri apparently believed that this infamous crime would provide him a platform from which to describe his "victimization" by lawyers, real estate firms, and the manufacturers of monosodium glutamate. (Brazil, Rosenfeld, and Williams, 1993, p. A1) When we consider the sort of characters interviewed on the afternoon talk shows (sometimes characterized as "freak of the week"), it is only slightly absurd that Ferri thought this brutal act would provide him a national soap box. Local coverage of this brutal crime and its aftermath was dramatic, continuous, and heart-rending.

This wasn't the end of the media-induced bloodshed. Less than two weeks later, in Antioch, California, a suburb of San Francisco, Joel Souza murdered his children, then killed himself as an act of revenge against his estranged wife. When police searched a van that Souza had rented, they found a copy of a July 4th newspaper with headlines about Ferri's crime. Was the presence of the newspaper a coincidence? Apparently not — the newspaper was already a week old when Souza rented the van, so Souza had been holding on to this reminder of Ferri's fame when he made the decision to murder. (Hallissy, 1993, p. A18)

A Holiday Killing Spree. (1988, January 11). Time. p. 35.

Annin, P., (1991, October 28). 'You Could See the Hate'. Newsweek. p. 35.

Another AK-47 Massacre. (1989, September 25). Time. p. 29.

Another Fatal Attraction. (1988, February 29). Time. p. 49.

Assault Weapons: A Setback for the NRA. (1990, June 4). Newsweek. p. 53.

Baker, J. N., Joseph, N., & Cerio, G., (1989, January 30). Death on the Playground. Newsweek. p. 35.

Baker, J. N., & Murr, A.. (1989, September 25). 'I Told Them I'd Be Back'. Newsweek. p. 22.

Brazil, E., Rosenfeld, S., & Williams, L. (1993, July 4). Gunman's goal: Kill, then tell all on 'Oprah'. San Francisco Examiner. p. A1.

Carrico-Martin, S. (1991, October 28). How I Bought a Gun in 40 Minutes. Time. p. 34.

Church, G. J., Beaty, J., Shannon, E., & Woodbury, R. (1989, February 6). The Other Arms Race. Time. pp. 20-26.

Convicted. Larry Mahoney. (1990, January 1). Time. p. 74.

Hackett, G., & Gonzalez, D. L. (1987, January 12). San Juan's Towering Inferno. Newsweek. p. 24.

Hackett, G., & Lerner, M. A. (1987, December 21). Settling A Score. Newsweek. p. 43.

Hallissy, E. (1993, July 13, 1993). Behind Killer Dad's Deadly Rampage. San Francisco Chronicle. pp. A17-A18.

Hammer, J. (1989, February 20). The Impact of Stockton. Newsweek. p. 8.

Harrison, E. (1989, September 15). Gunman Kills 7 and Himself at Kentucky Plant. Los Angeles Times. p. A1.

Johnson, T. E., & Shapiro, D. (1988, January 11). A Mass Murder in Arkansas. Newsweek. p. 20.

Kentucky Killer's Weird Collection. (1989, September 16). San Francisco Chronicle. p. A2.

Lacayo, R., & Shannon, E. (1989, February 6). Running Guns up the Interstate. Time. p. 24.

Lamar, J. V., & Duffy, M. (1989, March 27). Gunning for Assault Rifles. Time. p. 39.

Leo, J., & Griggs, L. (1984, July 30). Sudden Death. Time. pp. 90-91.

Magnuson, E., Hannifin, J., & Seufert, N. (1987, December 21). David Burke's Deadly Revenge. Time. p. 30.

Magnuson, E., & Mehta, N. S. (1990, April 9). The Devil Made Him Do It. Time. p. 38.

Magnuson, E., Leviton, J. & Riley, M. (1989, July 17). Seven Deadly Days. Time. pp. 30-60.

Magnuson, E., Leviton, J. & Riley, M. (1989, July 17). Suicides: The Gun Factor. Time. p. 61.

Massacre In a Mall. (1987, May 4). Time. p. 27.

Mathews, J., & Devroy, A. (1989, September 16). Killing spree fails to sway Bush. Santa Rosa (Cal.) Press-Democrat. p. A3.

Milestones. (1991, September 2). Time. p. 63.

Murder, 96 Counts. (1987, January 26). Time. p. 23.

No Lessons Learned. (1991, October 28). Time. p. 33.

Rossmann, R. (1989, April 16). Killing suspect's daughters found — 2 dead, 1 alive. Santa Rosa (Cal.) Press-Democrat. p. A1.

Rowan, R. (1991, April 8). A Time to Kill, And a Time to Heal. Time. pp. 11-12.

Salholz, E., & King, P. (1988, May 30). 'I Have Hurt Some Children'. Newsweek. p. 40.

Salholz, E., & King, P. (1988, June 13). Falling Through the Cracks. Newsweek. pp. 33-34.

Sanders, A. L., Kroon, R., & Wyss, D. (1989, May 1). Bringing Them Back to Justice. Time. p. 42.

Sandza, R., Lerner, M. A. & Gonzalez, D. L. (1989, March 27). The NRA Comes Under the Gun. Newsweek. pp. 28-30.

Sentenced. William Bryan Cruse. (1989, August 7). Time. p. 4.

Simon Rodia, 90, Tower Builder. (1965, July 20). New York Times. p. 20.

Slaughter in a School Yard. (1989, January 30). Time. p. 29.

Smothers, R. (1990, June 20). Hazy Records Helped Florida Gunman Buy Arms. New York Times. p. A17.

Strasser, S., & McAlevey, P. (1984, July 30). Murder at McDonald's. Newsweek. pp. 30-31.

Wilentz, A., & Diedrich, B. (1987, January 12). 'A New Year We'll Never Forget'. Time. pp. 19-20.

Woodbury, R. (1991, October 28). Ten Minutes in Hell. Time. pp. 31-34.

Worker on Disability Leave Kills 7, Then Himself, in Printing Plant. (1989, September 15). New York Times. p. A12.

'You Know I'm Guilty — Kill Me'. (1989, November 11). Time. p.

37.

Undigested Wire Service Stories

Inman, W. H. (1989, September 16). Wesbecker's rampage is boon to gun dealers. UPI.

Inman, W. H. (1989, September 16). Gunman's assault weapon ordered through the mail a $349. UPI.

Scholarly Journals

Cairns, E. (1990). Impact of Television News Exposure on Children's Perceptions of Violence in Northern Ireland. Journal of Social Psychology, 130:4, 447-452.

Harris, M. B. (1992). Television Viewing, Aggression, and Ethnicity. Psychological Reports, 70:1, 137-138.

Lester, D. (1989). Media Violence and Suicide and Homicide Rates. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 69:3 894.

Price, J. H., Merrill, E. A., & Clause, M. E. (1992). The Depiction of Guns on Prime Time Television. Journal of School Health, 62:1, 15-18.

Wood, W., Wong, F. Y. & Chachere, J. G. (1991) Effects of Media

Violence on Viewers' Aggression in Unconstrained Social Interaction. Psychological

Bulletin, 109:3, 371-383.

Films

Kasdan, L. (Director). (1991). Grand Canyon [Film]. Twentieth

Century Fox.

Books & Encyclopedias

Allen, W. B. (Ed.), (1983). The Works of Fisher Ames. Indianapolis: LibertyClassics.

Bengtson, H. (Ed.), (1968). The Greeks and the Persians: From the Sixth to the Fourth Centuries, (J. Conway Trans.). New York: Delacorte Press.

Borden, Lizzie Andrew (1963). Encyclopedia Americana, 4:266. Chicago: Americana Corp.

Coleman-Norton, P. R. (1963). Ephesus. Encyclopedia Americana, 10:414. New York: Americana Corporation.

De Camp, L. S. (1963). The Ancient Engineers. New York: Ballantine Books.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (1992). Crime in the United States: 1991. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Hulteng, John L. (1981). Playing It Straight. Chester, CT: The Globe Pequot Press.

Klaidman, Stephen, & Beauchamp, Tom L. (1987). The Virtuous Journalist. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lambeth, Edmund B. (1986). Committed Journalism: An Ethic for the Profession. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Meyer, Philip (1987). Ethical Journalism. New York: Longman Inc.